As 2022 commences, the domestic security landscape continues to evolve and mutate. The COVID-19 pandemic, and our efforts to contain it, have upended many people’s way of life, causing enormous disruptions and forcing substantial economic and psychological hardship upon communities.

The pandemic has also led to a significant increase in the amount of time individuals spend online, socializing with others and attempting to make sense of their changing world, further deepening humans’ technological dependence. Meanwhile, climate change continues to present an enormous global challenge, with the much anticipated COP26 meeting being widely hailed a disappointment.

As our world continues to change, so does the domestic security threat. As society attempts to make sense of the COVID-19 pandemic, and communities suffer the economic fallout of its impact, vulnerable individuals and fragile communities will become increasingly susceptible to extremist ideology.

As distrust in governments and institutions continues to grow, and global challenges remain unmet, individuals will increasingly use online platforms to find like-minded individuals, developing networks to provide a sense of community, security, and identity. This deepening tribalism has the potential of fragmenting society into a patchwork of hostile, ideological communities.

The Global Jihadist Movement

Although it now receives less attention amongst the global community than it did during the peak periods of the Global War on Terrorism, or indeed, during the more recent years of ISIS’ prominence, the global jihadist movement continues to represent a substantial domestic threat, remaining one of the most lethal terrorist risks.

Despite the apparent demotion of the Islamist terror threat to a second-tier priority amid the United States’ shift in focus to great power competition and pandemic response, the threat of jihadi terrorism remains active. Whilst recent years have seen several of the most notable international jihadi terrorist organizations, including al-Qaeda and ISIS, weakened by the counter-terrorism efforts of western forces, many of their overseas offshoots and affiliates remain mobile.

Despite its abhorrence to many Muslims around the world, extremist Islamist ideology continues to resonate with radicalized individuals throughout the west. The Taliban’s recapture of Afghanistan represents a major propaganda victory for the global jihadi movement.

Moreover, the Taliban’s severe approach to counterinsurgency warfare has inflamed the country’s security crisis, exacerbating the risk of civil war. This potential conflict may find itself joining the array of other armed campaigns waged by Islamists throughout Africa, further expanding the potential of overseas battlefields to become magnets for foreign fighters from the West.

This internationalization of the jihadist terrorist effort is a major security threat, motivating domestic extremists to take violent action against their own societies and providing combat-training for western recruits, many of whom will evade capture in returning to their home countries.

Right-Wing Extremism

After the September 11 attacks, the United States’ national security community maintained a two-decades-long focus on combating international jihadist terrorism. Estimates as to the cost of this global endeavor reach as high as $8 trillion, and by the end of 2019, the United States was engaged in counter-terrorism missions across 80 countries. Given this extraordinary focus on combatting the global Islamist terror threat, it is perhaps unsurprising that combatting the rapid expansion of domestic, far-right extremism remained somewhat peripheral.

White supremacists, neo-Nazis, and other right-wing extremist actors, groups, and ideologies now present a clear domestic threat. Racism, xenophobia, anti-Semitism, and white supremacy are increasingly motivating attacks throughout the West. Indeed, the Global Terrorism Index has reported a 320% increase in far-right terrorist attacks between 2013 and 2018, many of which were concentrated throughout Western Europe, North America, and Oceania, in cities such as Pittsburgh, El Paso, Oslo, and Christchurch.

The armed insurrection at the Capitol on 6 January 2021 demonstrated the extent of the right-wing extremism threat within the United States. The attack involved over 100 injuries and caused $30 million in damages. It also provided a showcase of the various groups, beliefs, and ideologies that permeate the broader right-wing extremist milieu within the United States.

Among these was the QAnon movement, an online meme that has evolved into one of the most influential conspiracy theories in the United States. The iconography of the movement was on display throughout the Capitol attack, on signs, banners, and clothing. Indeed, QAnon is becoming increasingly pervasive throughout the broader conservative movement, with over half of Republicans saying that at least “some parts” of the QAnon worldview are accurate.

In 2019, the Federal Bureau of Investigation drew attention to the radical adherents of QAnon as a domestic terrorism threat. Certainly, their core belief in a powerful and secretive global cabal of nefarious, Satan-worshiping elites certainly has the potential to incite other violent actions.

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has injected an array of novel and outlandish conspiracy theories into the extremist milieu of the far-right. These theories often form part of elaborate mis- and disinformation campaigns involving government corruption, social control, and even depopulation. These beliefs can serve as powerful catalysts for radicalization and violent extremist action.

Anti-Technology Radicalism, Eco-Fascism, and the War on Civilization

Several of these pandemic-led conspiracy narratives involve an obsession with recently introduced technologies, including mobile passports, mRNA vaccines, human microchip implants, and 5G telecommunication systems. As of now, opposition to these technologies is largely organized in relation to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the various conspiracy theories surrounding it.

However, security experts have warned that these beliefs, and the actions they have incited, including the destruction of vaccine vials and 5G communication towers, have the potential of morphing into a broader, unified movement against technology; this form of extremism has been referred to as anti-technology radicalism.

Indeed, as artificial intelligence, robotics, and the other emerging technologies of the fourth industrial revolution further exacerbate existing social and economic grievances, including job insecurity and a deepening wealth gap, it is possible the anti-technology movement will expand into a fully-fledged domestic security threat.

This aversion to technological advances is also connected to a growing form of extreme eco-fascism. As climate change creates new social stresses, and individuals become increasingly frustrated by government inaction, right-wing extremists are adapting environmental concerns to fit their narratives and worldview. This is achieved by adopting environmental language for nativist, nationalist, and racist ends, emphasizing notions of “blood and soil”: the idea that particular ethnocultural groups share a symbiotic connection with their homeland.

Through the lens of these right-wing extremists, the answer to the environmental crisis is the strengthening of borders, the increased marginalization of racial minorities, and an obsessive focus on ethnocultural identity.

Both the El Paso and Christchurch terrorists alluded to eco-fascist ideology in their manifestos, and indeed both anti-technology radicalism and eco-fascism feed into a broader neo-Luddite movement encompassing an array of other concerns, including urbanization, consumerism, and industrialization. This anti-technology, neo-Luddite movement will continue to recruit followers as the climate crisis expands and emergent technologies arise. Indeed, as researchers have noted, it may well already be set on an escalatory path toward a war against techno-industrial civilization itself.

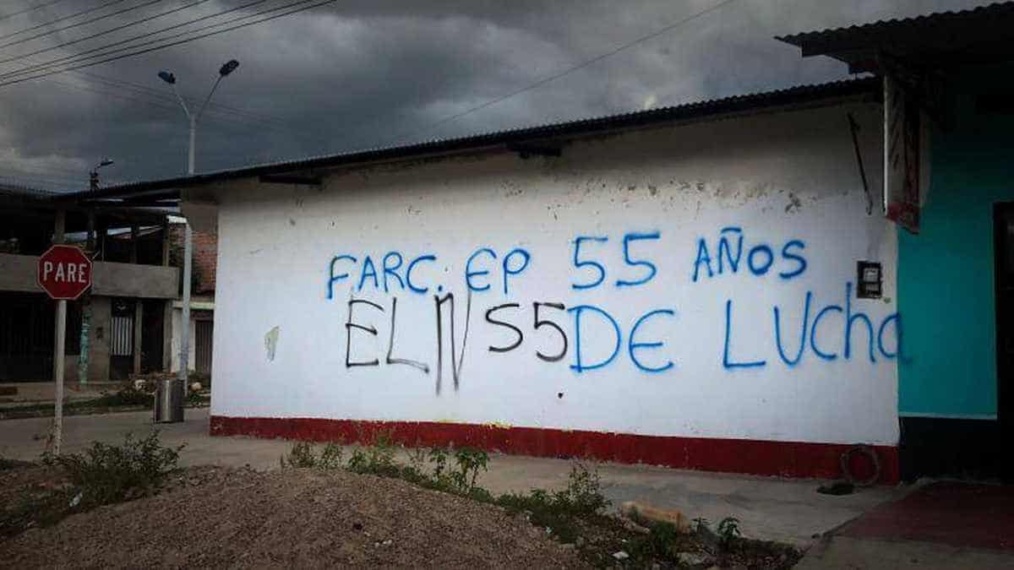

Left-Wing Extremism

Whilst jihadists and right-wing extremists most likely remain the strongest and most lethal domestic security threat, the uncertainty and disruption engendered by the COVID-19 pandemic, economic instability, climate change, and emergent technologies may activate largely dormant forms of political violence, including left-wing extremism.

As economic insecurity and social disruption is increasingly forced upon individuals and communities, they will be vulnerable to left-wing narratives that emphasize violent action as a means to redress wealth inequality, government incompetence, and corporate malfeasance.

Currently, left-wing extremists, including violent anarchists, radical strands of Black nationalism, and antifa, present a significantly weaker threat than jihadists or right-wing extremists. Nonetheless, violent far-left actors have demonstrated their ability to incite civil unrest.

Recent history has demonstrated that far-left actors are willing to use improvised weapons, such as projectiles, commercial fireworks, and petrol bombs to target police, property, and other avatars of perceived social injustice. Indeed, firearms are increasingly appearing at left-wing protests, and recent arson and car ramming attacks could suggest left-wing extremists are growing more willing to deploy violence in service of their ideological agenda.

Reciprocal Radicalization and Fringe Fluidity

Whilst the increase in the threat of far-left violence is driven, in large part, by individuals’ growing sense of social and economic grievance, and its capture by extremist actors, the expansion of the left-wing extremist threat may also be connected to the recent upsurge in far-right violence. This process, wherein extremist groups fuel one another’s rhetoric and behavior, is known amongst researchers as reciprocal radicalization.

This process, also known as co-radicalization, cumulative extremism, and interactive escalation, describes a situation wherein extremists groups mutually reinforce the radicalization of their opponent groups, producing a self-feeding cycle of hatred, intolerance, and resentment.

Whilst the process was first described by researchers investigating the relationship between militant Islamists and anti-Islamists, this phenomenon of reciprocal radicalization also feeds the increasing hostilities seen in confrontations between far-left and far-right actors.

However, security experts warn that the prevalence of these simple ideological dichotomies in describing the extremist landscape, such as those drawn in descriptions of the relationship between militant Islamists and anti-Islamists, or left-wing and right-wing extremists, is deeply limiting.

Increasingly, lone actors and small groups of domestic extremists, these being the most likely perpetrators of violent attacks within the United States, are motivated by diverse ideological amalgamations of extremist beliefs. These extremists are motivated by so-called “salad bar” ideologies that draw from numerous, and sometimes even contradictory, ideological foundations.

The adoption of pro-environmental rhetoric amongst right-wing extremists is a classic example of this absence of ideological rigidity, a phenomenon that has been labeled by researchers as fringe fluidity and ideological convergence. Here, the lines between left-wing ideology, of which pro-environmental beliefs have long been associated, and right-wing ideology merge together.

Indeed, a number of prominent terrorist and extremist actors have demonstrated this ideological fluidity, such as: Andrew Anglin, the founder of The Daily Stormer, one of the most popular neo-Nazi websites, was once a devoted vegan and self-described anti-racist who advocated a range of left-wing causes; Nicholas Young, a fanatic supporter of militant Islamism sentenced to fifteen years in prison for aiding ISIS, was also a devoted neo-Nazi; and Adam Gadahn, the American al-Qaeda spokesman who was once one of the most wanted terrorists in the world, experimented with Evangelical Christianity before converting to radical Islam.

This fringe fluidity, powerfully exemplified by the far-right’s growing fetishization of militant Islam, represents a significant challenge to security experts’ traditional understanding of extremist ideology. Its growing prominence amongst violent extremist actors is a concerning trend. Iindeed their attempts to reconcile disparate, and even oppositional, elements of different ideologies, including those drawn from jihadism, neo-Nazism, anti-technology radicalism, eco-fascism, and left-wing extremism, demands a deep overhaul of the long-held assumptions and established analytic frameworks that have dominated security experts’ efforts to combat violent extremism.

Conclusions

As mistrust in government, institutions, and the established social order continues to grow, fueled by the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic, the acceleration of the global climate crisis, and the disruption of emerging technologies, individuals and communities become increasingly vulnerable to radicalization.

Indeed, according to the National Intelligence Council’s Global Trends 2040 report, published in March 2021, “large segments of the global population are becoming wary of institutions and governments that they see as unwilling or unable to address their needs. People are gravitating to familiar and like-minded groups for community and security, including ethnic, religious, and cultural identities as well as groupings around interests and causes, such as environmentalism.” This trend, should it continue, will drive violence, extremism, and terrorism within the United States and beyond, as ideological groups increasingly come to see the world in terms of “us versus them.”

The U.S. government should work, in conjunction with the private sector and civil society organizations, to counter these trends. Efforts must be made to address the grievances that fuel extremist recruitment, including the various socioeconomic and psychological stresses that have been amplified by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Currently, the most lethal threat remains that posed by jihadists and right-wing extremists. Nonetheless, security officials must remain cognizant of other domestic security threats, including those presented by eco-fascists, anti-technology radicals, and left-wing extremists. These new potential security threats will likely be empowered by government inaction on climate change and the disruptive impact of emergent technologies.

Moreover, domestic terrorist attacks are increasingly perpetrated by lone individuals or small extremist groups. These actors are often motivated by incoherent amalgamations of ideological belief, challenging security experts’ established understanding of extremist ideology. Efforts must be made to expand and adapt the methods used to counter this growing form of extremism; indeed a major overhaul of long-established counter-terrorism frameworks may be demanded.

As global and domestic circumstances change, driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, socioeconomic disruption, climate change, and the impact of new technologies, the threat of domestic extremism will rise. To address this challenge, the United States must work to protect vulnerable individuals and communities, providing support that helps mitigate the allure of extremist ideology. Nonetheless, the U.S. should sustain its commitment to countering jihadism and right-wing extremism, whilst also developing its ability to adapt to new security threats and the emergence of new forms of extremism.

As 2022 commences, the domestic security landscape continues to evolve, driven by the disruption and instability of our changing world. Should the U.S. hope to counter this upheaval, and its exploitation by extremist forces, then it must work to revitalize broken communities, rebuild public trust, and restore a sense of civic unity.

Oliver Alexander Crisp, Counter-Terrorism Research Fellow