One of Latin America’s darkest periods began in 1865 — around the time that the American Civil War was drawing to a close — but its wounds still have not healed. The mid-19th century Paraguayan War saw its namesake on one side and a triple alliance of Brazil, Argentina, and Uruguay on the other. Latin America looked quite different then. It has long been a place in flux politically, economically, and geographically speaking. But, this conflict altered rudimental perceptions of the continent. Its scars in South America run deep.

In 1862, just three years before the start of the war, Solano Lopez became the country’s second president.

In 1865 Argentina was a newly independent nation. It won its independence in an 1810 war with Spain led by Jose de San Martin. Uruguay was part of Argentina, as part of the United Provinces of the Rio de la Plata, which was then conquered by Brazil and became independent in 1824. This, at the conclusion of Brazil and Argentina’s war for it. Brazil gained its independence from Portugal in 1822 but kept its royal family as it became an Empire. It often intervened in the domestic affairs of its South American neighbors.

Paraguay of today versus Paraguay of 150 years ago is a study in contrasts. It became independent from Spain in 1811. It instituted a military junta to control the country. Paraguay developed an economy, arguably becoming the most advanced South America country at the time. It used British support and know-how to develop industry and improve infrastructure. In 1862, just three years before the start of the war, Solano Lopez became the country’s second president.

Wikipedia: Brazilian Soldiers at the end of the war, including Corporal Chico Diabo (sitting down, third from left), who killed Paraguayan dictator Solano Lopez.

Paraguay like its 19th-century industrialized society peers needed access to production inputs, labor, and ports from which it could ship products. As a landlocked country, Paraguay’s only choice to gain access to the sea was to expand. Thus, Lopez started his expansionist plan and in 1865 attacked Brazil and Argentina with great success. The two attacked nations organized a joint war effort, and with Uruguay, created the Triple Alliance. Initially, the commander of their armies was Argentinian President Bartolome Mitre.

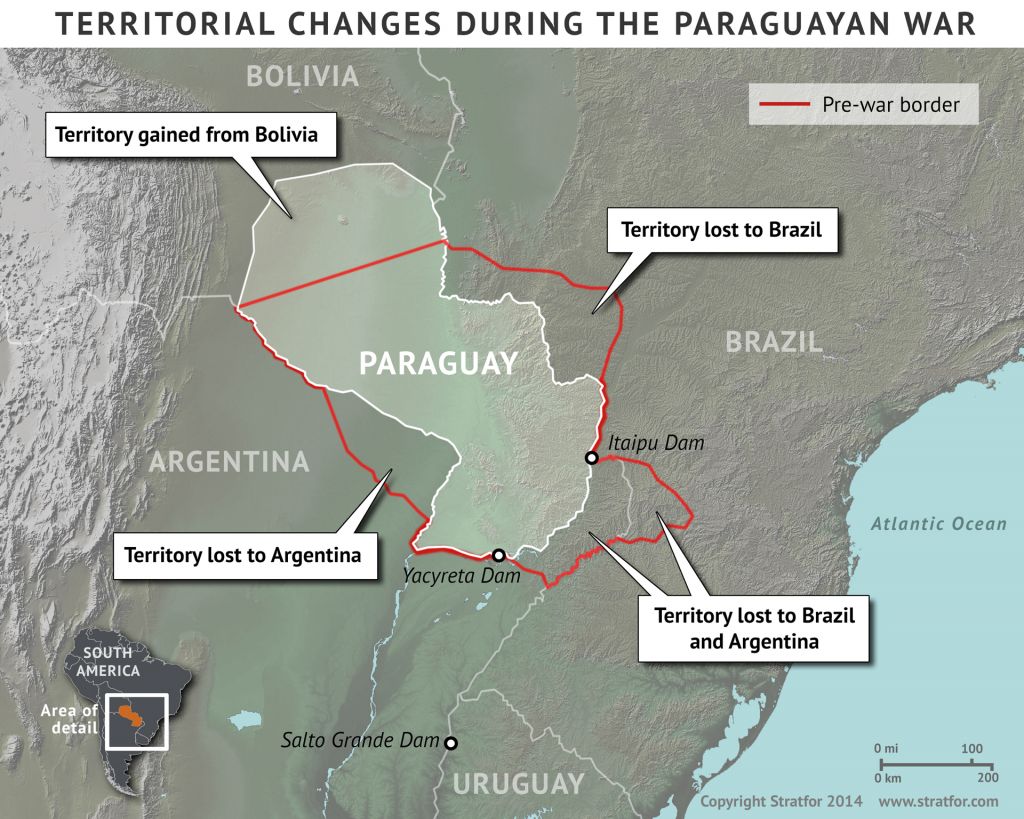

Brazil and Argentina annexed considerable portions of Paraguayan territory in the peace treaty following the end of the war.

Wikipedia: Battle of Riachuelo by Victor Meirelles, the turning point of the Paraguayan War

During the war’s first phase Paraguay was on the offensive. In February 1867 Mitre stepped down as the allied commander. He was replaced by Brazilian Army commander Luis Alves de Lima e Silva, aka the Duke of Caxias. Caxias was nominated Brazilian commander in October of the previous year. His first command halted the Brazilian army’s advance. Thereafter, he completely reorganized and restructured the allied military. Consequently, when he restarted the offensive in July 1867, the allied forces won one victory after another. This momentum allowed them to take Asunción, Paraguay’s capital, in January of 1869, defeating the Paraguayan forces. With the war seemingly won, Caxias — who was old and tired — relinquished his command of the allied war effort.

The Triple Alliance governments were unsatisfied and continued the war. They nominated the Count D’Eu, Brazilian Emperor Peter II’s son-in-law, to command their military forces. While Lopez refused to surrender, his resistance didn’t amount to much. With the army depleted, women, children and the wounded were left to fight on. What followed is one of the darkest moments in Brazilian history. Argentina and Uruguay decimated the Paraguayan population and destroyed the country. Brazil and Argentina annexed considerable portions of Paraguayan territory in the peace treaty following the end of the war.

This conflict altered rudimental perceptions of the continent.

The effect on Paraguay cannot be overstated. The most harrowing statistics indicate that 60% of Paraguay’s population, and 90% of its men, fell victim to combat, disease, or starvation. Paraguay was set back decades in its development and industrialization. This lag remains responsible for current economic and social problems.

The war is infrequently discussed outside of South America, but it’s a terrible chapter which reshaped its power balance ever after. Paraguay struggles with criminality, bootleggers, and drug traffickers to this day. It is poorer and less developed than its neighbors. It’s a lesson in the comprehension of a nation’s struggle. Often undermining characteristics result from occurrences decades or even centuries in the past. It is a vital reminder to keep human rights in the fore, and not forget its victims, lest they reoccur. Meanwhile, the wounds are far from healed, Paraguay may never recover fully, and it resurfaces often in relations between the four countries.

Roberto Malta, is a Brazilian born, George Mason University student pursuing a B.A. in Global Affairs, with minors in History and Economics.