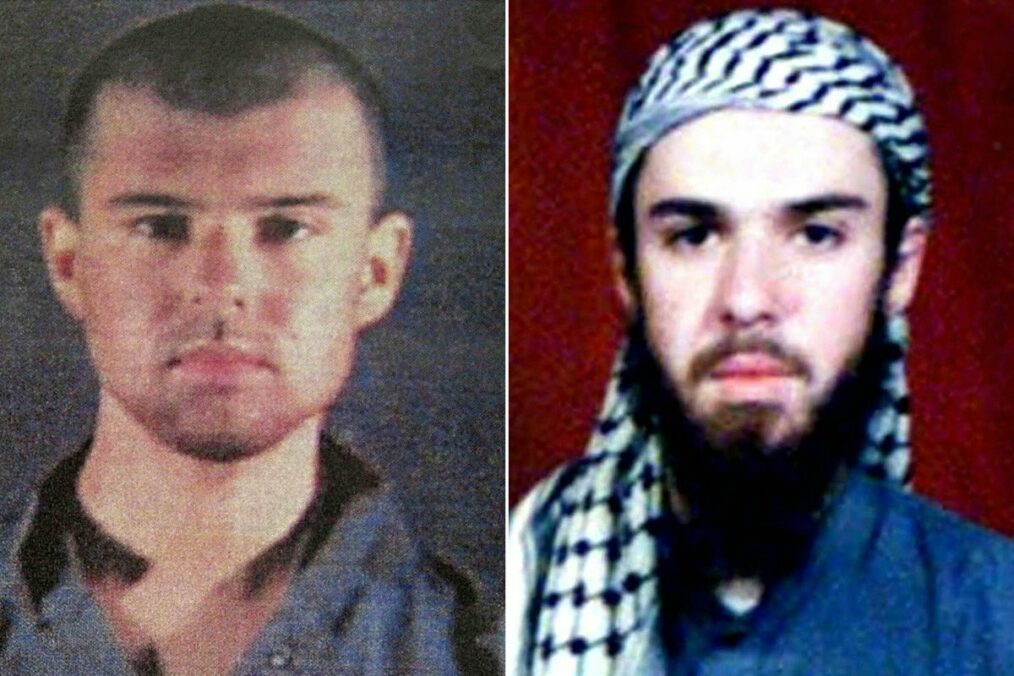

John Walker Lindh in January 2002. Image Courtesy of the Associated Press.

On February 9, 1981, the man who would become known as “The American Taliban” was born in Washington, D.C. John Phillip Walker Lindh is a former foreign fighter for the Taliban, often known for his involvement in the Battle of Qula–i-Jangi; a Taliban uprising which resulted in the death of CIA Officer Johnny “Mike” Span. After serving 17 years of his 20-year sentence, Lindh was released from prison under supervisory conditions on May 23, 2019.

Lindh was raised Catholic in Marino County, California, just outside of San Francisco. He is described as a bookish teenager who began studying Islam and the Middle East through his high schools’ alternative and self-directed study programs. Lindh’s initial interest in Islam has been linked to watching the Spike Lee film, “Malcolm X”, when he was 12.

However, his earnest interest in the faith and such related topics of study could have been marred by the extracurricular research Lindh engaged in as an active user of Internet Relay Chat rooms (IRC). Using the alternate identity “Mujahid”, Lindh communicated with others online largely about hip-hop music and racial topics. However, it is known that there are IRCs dedicated to the Taliban and Jihad, which indicates such online activity could have exposed Lindh to radical ideas.

Lindh officially converted to Islam at the age of 16, around the same time he dropped out of high school and was reported as participating in the IRCs. He also began attending mosques in Mill Valley and San Francisco. He reportedly became involved with Tablighi Jamaat, a Sunni missionary group, at this time. This group had not previously been associated with al-Qaeda or the Taliban, but has recently been investigated for links to radicalized militants. While the group was not tied to radicalization at the time of Lindh’s capture, the fact that it has been investigated in more recent years suggests Lindh may have been influenced by this group’s radical ideas.

Throughout his adolescence, Lindh’s parents experienced conflict within their marriage eventually leading to their divorce in 1999. His family instability could be noted as another influence in Lindh’s turn to Islam. His participation in the online chat rooms containing extremist messaging could also have infiltrated his ideology and affected his scholarly interest in the Middle East.

At the age of 17, Lindh decided to leave the U.S. for Yemen, with hopes to study Arabic so that he could read the Qur’an in its original language. He then traveled to Pakistan in 2000, where it is said he encountered extremist groups and training that ultimately influenced his decision to move to Afghanistan and join the Taliban.

However, Lindh claims his original motivation for joining the Taliban came from a desire to fight the mistreatment of civilians by the Northern Alliance. He reported hearing about this mistreatment through various stories; While it is not clear which outlets or messages Lindh received such information, this case illuminates the importance of eliminating misinformation and propaganda from public discourse. This can be achieved through means such as media literacy programs or more robust online security and privacy measures. Since 75% of domestic jihadists knew or were in contact with another jihadist prior to becoming radicalized, it is likely that Lindh was influenced by the information shared with other users of his IRCs or people he met while traveling and studying in Yemen and Pakistan. Whether it be through online forums or verbal conversations with other extremists, misinformation is a dangerous contributor to radicalization and should continue to be a priority in counter-terrorism work.

Since Lindh’s capture, contradictory reports have emerged as to his motivations for joining the Taliban as well as his understanding of the consequences of his involvement. During his trial, Lindh condemned terrorism and indicated he never held the desire to fight against Americans. Other reports, such as one from the National Counterterrorism Center, claim that Lindh would continue to advocate for jihad and violent extremism. The confusion and lack of clarity around the context and details of such reports must be resolved quickly in order to gain a comprehensive understanding of the belief system Lindh currently holds after having spent 17 years in prison. This case exposes a large question the U.S. will face in the coming years, as more extremists and convicted terrorists are released back into society without certainty of the continued existence of dangerous ideology that could pose security risks in the future.

While there are no formal procedures for re-entry of convicted terrorists and sympathizers within the U.S. Justice system at this point, there are some recommendations and best practices set in place to deal with this increasingly prevalent situation. First, counseling focused on mental health and identification of the initial causes of radicalization can be recommended; This will not only aid the individual, such as Lindh, but also provide scholars and practitioners with a broader understanding of the life circumstances that can lead individuals vulnerable to extremist messaging.

In addition, existing re-entry programs for former prisoners involved with gangs could be modified in order to apply to violent extremists, with similar encouragement of study, job training, and programming elements. These programs could provide alternative life paths, sense of belonging, and new sources of information to help eliminate dependence and association with extremist narratives. Monitoring of compliance with such programs is necessary not only during their sentence but also upon release, ideally from mentors who have experienced a similar situation but have emerged de-radicalized.

The way in which the media and public reacted to Lindh’s initial case as well as his release should be used as an example when addressing the situation of Americans linked to terrorism reentering society. In both instances, headlines and sound bites were quick to villainize him and draw attention to his case. The recent terrorist attack in New Zealand comes to mind as an alternative example, when the Prime Minister, in an effort to reduce copycats and the fetishization of terrorism, refused to address the terrorist responsible and would not play the video of the attack. The narratives perpetuated by the media and popular discussion seem relevant to Lindh’s, and others who had become radicalized, return to society.

Since radicalization can stem from feelings of being an outsider or from being bullied, the mass public villainization of Lindh and other Americans linked to terrorist organizations seems to be counterproductive in achieving the type of reintegration that would be necessary to avoid a former prisoner’s retreat into extremist ideology. Not only will the systems and programs in place matter in how we handle re-entry, but the influence of the media and public discourse will matter as well, if not more.

Overall, the case of John Walker Lindh reminds America and the world not only of the spread of extremism but also the complex ways in which the world deals with extremism and terror. Through comprehensive research on an extremist’s path to radicalization, formalized mentorship and re-entry procedures, and an evaluation of the media’s influence on the re-entry process, the U.S. will have a chance to effectively manage the reintegration of former extremists back into society.

Nikki Hinshaw is a Counter-terrorism Research Fellow at Rise to Peace, a non-profit organization, and a current undergraduate student at Arizona State University. She has multiple years of experience in managing communications and marketing for organizations in all sectors, as well as in conducting research on topics relating to a variety of global social issues and public diplomacy policy and practice.