Introduction

United Nations peacekeeping operations are meant to help countries down the complex path of peace and reconciliation. Such peacekeeping missions are mandated by the United Nations Security Council (UNSC). A smaller subset of peacekeeping missions, stabilization operations, are not regulated by the UN Charter, but make-up three of the four largest ongoing peace operations. Their legitimacy rests between Chapter VI (peaceful settlement of disputes) and Chapter VII (use of force to restore peace), constituting the so-called “Chapter VI and a half.” These operations are a joint instrument of the Security Council (the highest political authority) and the Secretary-General, the highest administrative and functional authority of the organization.

Peacekeeping interventions are based on some strategic points, including legitimacy, burden sharing, and the possibility of deploying and integrating police forces and civilian personnel. The work that the UN conducts during peace operations is based on three fundamental principles, namely consent to intervention by countries in conflict, impartiality, and non-use of force (unless in self-defense or in defense of the mandate).

Thousands of “Blue Helmets,” the military body belonging to member states and “loaned” to UN missions, have over time morphed from mere observers limited to logistical and technical support to being assigned sensitive functions. They now operate more complex programs including political mediation, de-mining, public affairs and communication, protection and promotion of civil rights, and reintegration of combatants into society. The missions have thus become multidimensional and integrated.

Instability is not just a military fact, with a truce to guard or a cease-fire line to patrol, but has many causes. Stabilization operations thus include ever greater responsibilities, including the democratization of local institutions, economic and social development, environmental and natural resource protection, and the retraining of military forces, police, and prison services, according to modern, democratic criteria.

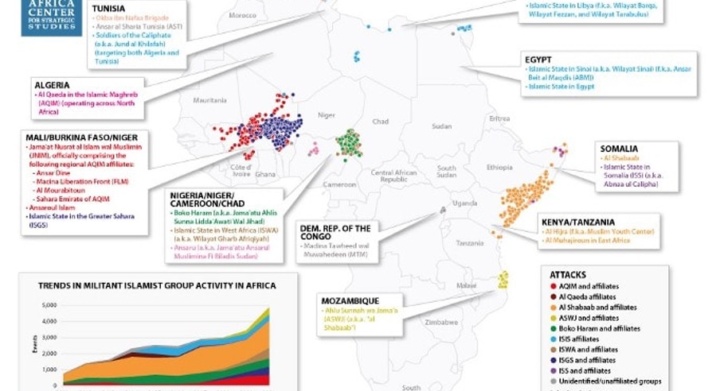

Africa

An example of these new and expanded functions are assistance and support missions, which are deployed in countries that have seen the total collapse (or almost total degradation) of state structures, countries such as Libya, Sierra Leone, Mali, Central Africa, and South Sudan. UN functions are also diversified and no longer restrained to patrolling truce lines. They have been involved in such diverse efforts as decolonization in Namibia, independence in Eritrea, protection of populations in the Democratic Republic of Congo, and the transition to democratic regimes after years of civil war in Angola, Mozambique, Central America, or West Africa. All these missions see not only the change in the profiles and structures of the missions but also their composition.

In West Africa, there are two very different missions, MINURSO and MINUSMA. The first aims to ensure, sooner or later, the holding of a regular referendum in the territories of Western Sahara, still disputed between Algeria, Morocco, and the local population. The mission has been active since 1991 and has 485 units, of which 245 are military.

MINUSMA, in Mali, started in 2013 shortly after the French military operation Serval, which halted the advance of Tuareg and other armed groups towards Bamako. Despite the collaboration with Operation Barkhane (formerly Serval) and the G5 of the Sahel, the area is still deeply unstable. MINUSMA’s annual budget exceeds one billion dollars and over 15,000 military personnel are deployed. The states that support the mission militarily are interested in containing the Malian crisis (Burkina Faso, Chad, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal).

As for Central Africa, MINUSCA is the stabilization mission of the Central African Republic. It was born in 2014, following the outbreak of civil war. Despite numerous peace agreements signed between parties, skirmishes and structural violence remain. The mission has an almost exclusively “regional” character since the troops present are Rwandan, Egyptian, Zambian, Cameroonian, and Senegalese. MONUSCO, on the other hand, is an operation that started in 2010 and aims to stabilize the Democratic Republic of Congo, devastated first by spillover from the Rwandan genocide of 1994 and then by its own wars from 1998 to 2003, which left over 5 million dead.

Additionally, three peacekeeping missions are active in the Horn of Africa, two in Sudan and one in South Sudan. The last one, UNMISS, was born in 2011 in South Sudan. After gaining independence, the country fell into a bloody civil war, dictated by patriotism and exploitation of ethnic tension, which have been intensifying since December 2013.

Analysis

Over the years, this United Nations instrument has been criticized extensively but has also received some positive feedback. Too often, in the initiatives of the powers that act in the name of the so-called international community, in which Africa, politically speaking, seems to be considered more an object than a real subject, the goal of “security” prevails. Very often, the issues of jihadism and human mobility towards Europe are considered separately from other issues plaguing African governments. There is a need for a repositioning of international diplomacy that considers the constant and progressive modification of the African geopolitical chessboard in the age of globalization.

The colonial and postcolonial models, to the test of facts, no longer represent a paradigm of reference in Africa for the control of aid institutions or even investments. The traditional partners of African countries (the former colonial powers) must now compete with the low index of “conditionality” strategies of emerging powers such as Brazil, China, India, Turkey, and Russia itself, which is reappearing in Africa after the withdrawal imposed, about thirty years ago, by the collapse of the Soviet Union.

It is precisely within these parameters that the United Nations, as an organism of peoples, is called to play an indispensable role. It is worth recalling what happened in the early 1960s with the wave of African independence movements. At that time, the UN, established as an organization after World War II with the aim of preventing future conflicts by replacing the ineffective League of Nations, played a politically relevant role.

In particular, the recognition of the principle of self-determination of peoples, sanctioned by the United Nations Charter, received a warm response. International law also outlawed war, in particular, due to Articles 2 & 4 of the Charter, declaring that member states must renounce war and resolve their conflicts.

To weigh negatively on these missions are a series of factors found in many investigations. The first of these factors is the lack of discipline among Blue Helmets and the fact that the contingents are sometimes composed of soldiers from countries where training standards are not adequate for modern crises in Africa. There have also been pervasive issues of sexual violence against women and minors.

Regardless, the United Nations has taken a central and irreplaceable role in the building of congenial international relations in the modern era. In the case of the African continent, the UN provides international legitimacy and an irreplaceable and indispensable forum for negotiation at global level on the issues of development, peace, and security.