The 19th edition of the World Summit on Counter-Terrorism was held from 9th to 12th September 2019 in Herzliya, a small maritime city just north of Tel Aviv, Israel.

I had the pleasure to live this unique opportunity, which gathers distinguished professionals working in the field of counter-terrorism under one roof, to facilitate the chance to exchange views and ideas on this very pertinent topic. The first two days of the Counter-Terrorism Summit are reserved for plenary sessions where members of the academia and policymakers set the scene for the Summit and illustrate how the issue is being dealt around the world.

During the 19th edition of the Summit, among the variety of aspects discussed, the growing issue of cyber terrorism, one which has become of very high concern in current times for many Western governments such as the United States, especially in terms of online radicalization.

In today’s times, many terrorist recruiters have moved to social media platforms (exactly the ones we use daily e.g. Telegram or Twitter) to target vulnerable subjects and attract them to join extremist organizations such as the Islamic State of Iraq and Levant (ISIL). For this reason, platforms such as Facebook have recruited over three hundred people to ensure that terrorist content of all kind does not appear on their platforms.

On the second day, the most remarkable and touching event took place as part of the Memorial for the victims of the 9/11 attacks. American Congressmen, Military Personnel and Secretaries of States and all the attendees joined in a minute of silence for the victims followed by both the American and Israeli anthems. This was an emotional moment where everybody put aside their personal identities to join a unique battle, winning over terrorism worldwide.

The third day marked the start of multiple workshops at the Interdisciplinary Center (IDC), Herzliya. Here, numerous topics related to various aspects of terrorism and counter-terrorism were discussed and recommendations were put forth by professionals, research fellows and members of the academia on ways to deal with this worldwide security threat.

Radicalization is among the most compelling issues, stressing the need for more policies able to detect subjects undertaking processes of radicalization. During the workshops, there was a repeated assertion regarding the need to control websites and social media platforms to identify extremist content and push it away from the access of youngsters and vulnerable subjects, a way of countering radicalization by denying terrorist the platform to access their audience.

The last day saw an interesting session on returning foreign terrorist fighters, an issue that demands more focus than it currently gets. However, it should not surprise how this phenomenon involves a variety of different aspects: from fueling the risks of radicalization to questions related to their integration in the society, but the most critical concern in this entire scheme of things is regarding children and women as foreign terrorist fighters often return with their families.

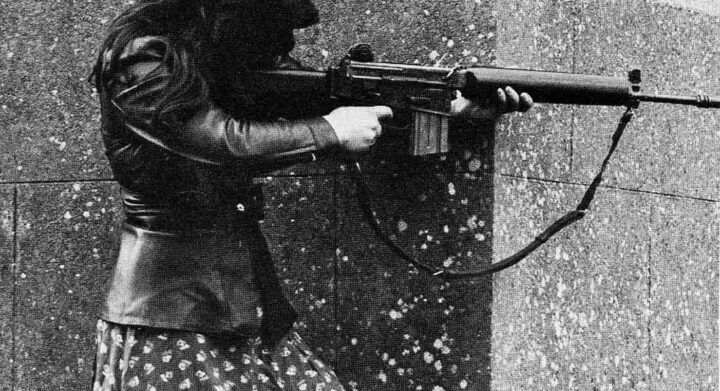

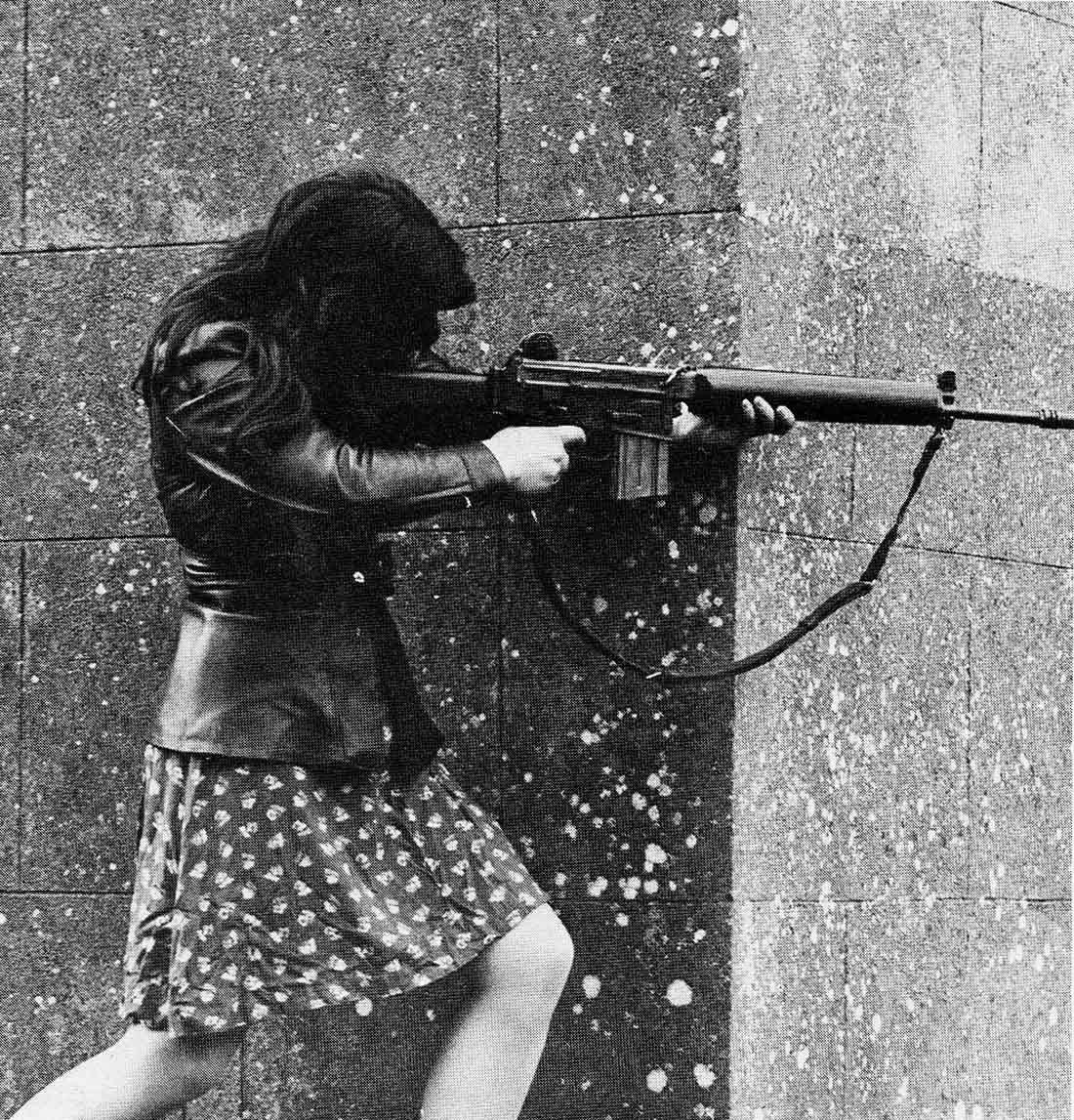

During the discussion, it was highlighted that besides the traumatic experience lived by the children, significant attention needs to be given to the role women have begun adopting over the past few years

During the discussion, it was highlighted that besides the traumatic experience lived by the children, significant attention needs to be given to the role women have begun adopting over the past few years. In this regard, Miss Devorah Margolin provided a thorough explanation on how the role of women has shifted from “staying at home” as wives of the fighters to “fighting on the field”, thus falling into the radar of many extremist organizations. Under these circumstances, it is crucial to remember that women have always been seen part of any conflict, though this role was previously limited to the domestic environment, with women being mothers and wives of the soldiers, but also nurses taking care of the casualties in a conflict.

The closing keynote address of the Summit highlighted on how the Islamic State might have been defeated geographically, but the challenge now is to remove its remaining signs around the world, as remnants of the group are still operating in the Middle East and some other parts of the world.

Finally, the Summit drew the attention to other emerging extremist organizations that are expanding their activities and gaining power in Africa and Lebanon, including Hezbollah and Boko Haram.

The stunning memento of this Summit is definitely the presence of a large number of people from different backgrounds, who gathered together with a sole goal of winning the global fight against terrorism.

Everybody can do something about terrorism, even a single word can help millions of people and we shall not forget this.

Not only is the Summit an opportunity to keep updated on counter-terrorism measures being applied around the world, but also the presence of students, professionals, policymakers or retired fellows suggests that counter-terrorism is not only a job but a mission to share among countries and regions of the world.

Everybody can do something about terrorism, even a single word can help millions of people and we shall not forget this.