U.S. War in Afghanistan: Review of the Previous Strategy:

2001-2013

The launch of Operation Enduring Freedom in October 2001 marked the start of US involvement in Afghanistan. The operation consisted mainly of airstrikes but also included a special operations force of roughly 1,000 later joined by 1,300 Marines. The primary goal was to support Northern Alliance and Pashtun anti-Taliban fighters[1].

In December 2001, the Taliban fled Kandahar, effectively ending their regime. From this point on US forces focused on raiding suspected Taliban and Al-Qaeda villages, until an end to major combat was declared in May 2003[2]. The US continued to carry out raids against insurgent violence until 2005 when they considered the insurgency defeated and turned control to NATO and ISAF forces2. Immediately thereafter, Afghanistan saw an increase in insurgent violence and the US decided to keep 30,000-40,000 troops in Afghanistan through the rest of the Bush Administration[3].

In March 2009, soon after taking office, President Obama added 21,000 troops to that force3. That December he deployed 30,000 more and introduced a plan to begin a withdrawal in 2011 and complete it by 20143.

In keeping with this plan, and given that the killing of Osama bin Laden accomplished a key US objective, President Obama announced in June 2011 that US forces would fall to 90,000 by the end of the year, and then drop to 68,000 by September 20123. In February 2013, he revealed plans to reduce the overall troop levels to 34,000 by February 20143.

2014-2016

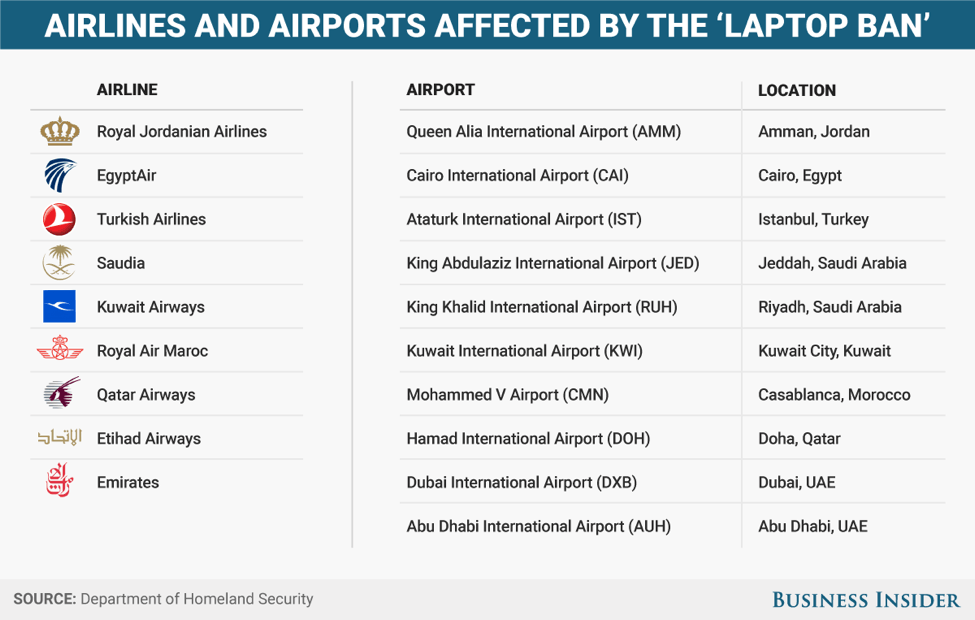

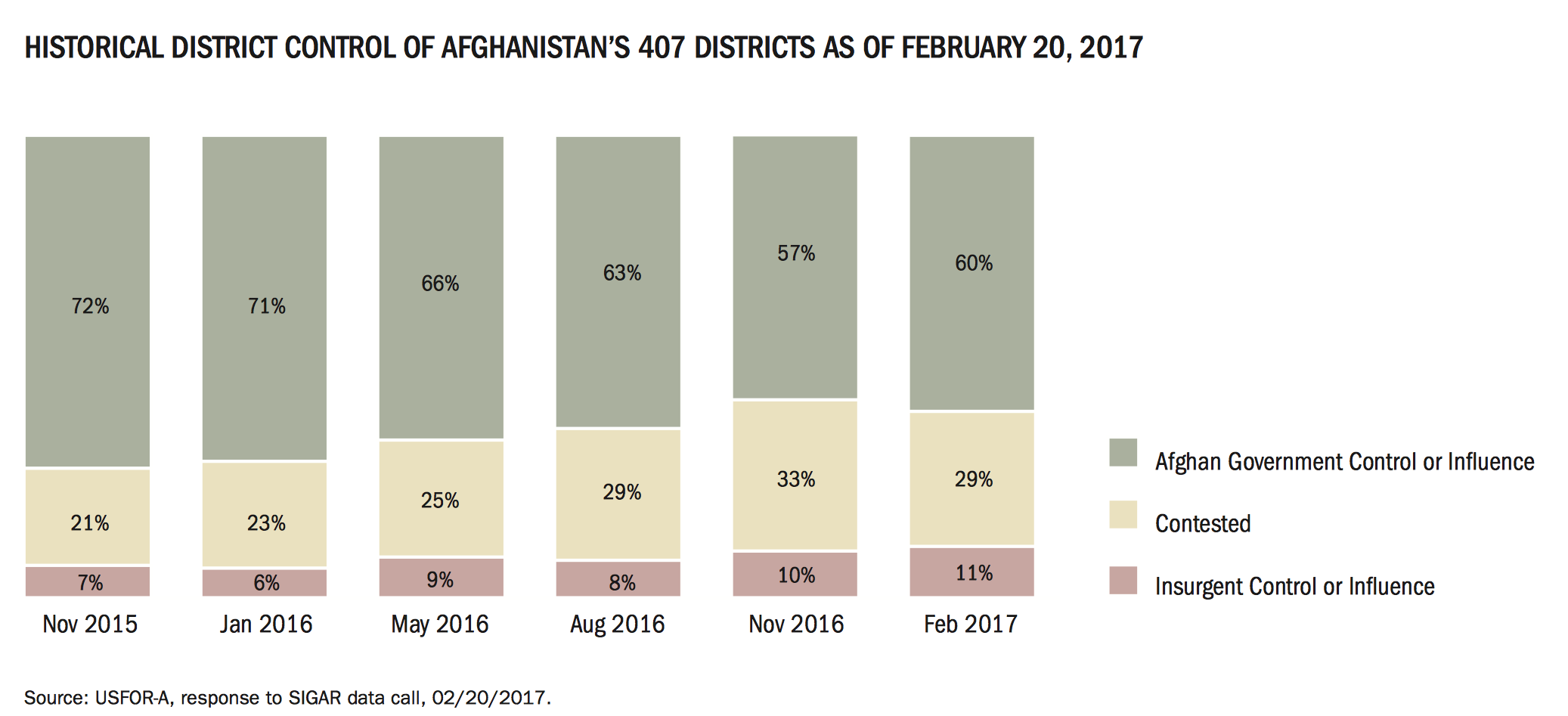

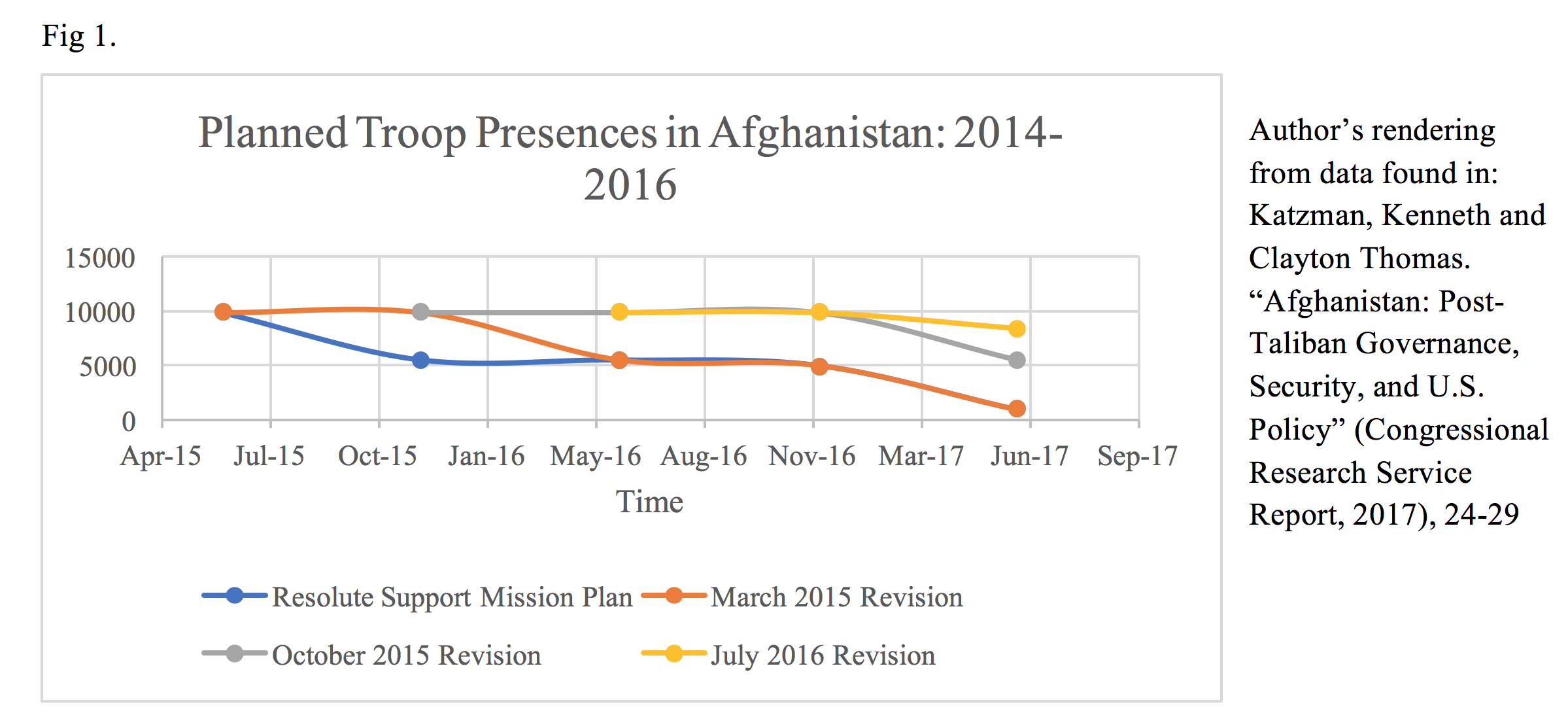

From that point on, the focus in Afghanistan was on US withdrawal. The Resolute Support Mission sought to decrease US troops in Afghanistan to 9,800 in 2015, then to 5,000 in 2016 and finally to 1,000 troops from 2016 onwards3. However, the Islamic State’s surge in Iraq along with worrying Taliban gains in Helmand Province created concern that, without adequate support, Afghanistan’s security could be in jeopardy3. With this in mind, the Obama administration changed plans in March 2015, opting to keep 9,800 troops in Afghanistan for all of 2015 and reduce to 5,500 throughout 20163. In October of that same year, it was decided that the troop level would instead remain at 9,800 through the end of 2016 and then drop to 5,500 from then onwards3. In July 2016, the Obama administration made its final revision, deciding to leave 8,400 troops in Afghanistan post-2016, rather than 5,500 (see fig. 1).

Figure 1

Current Concerns

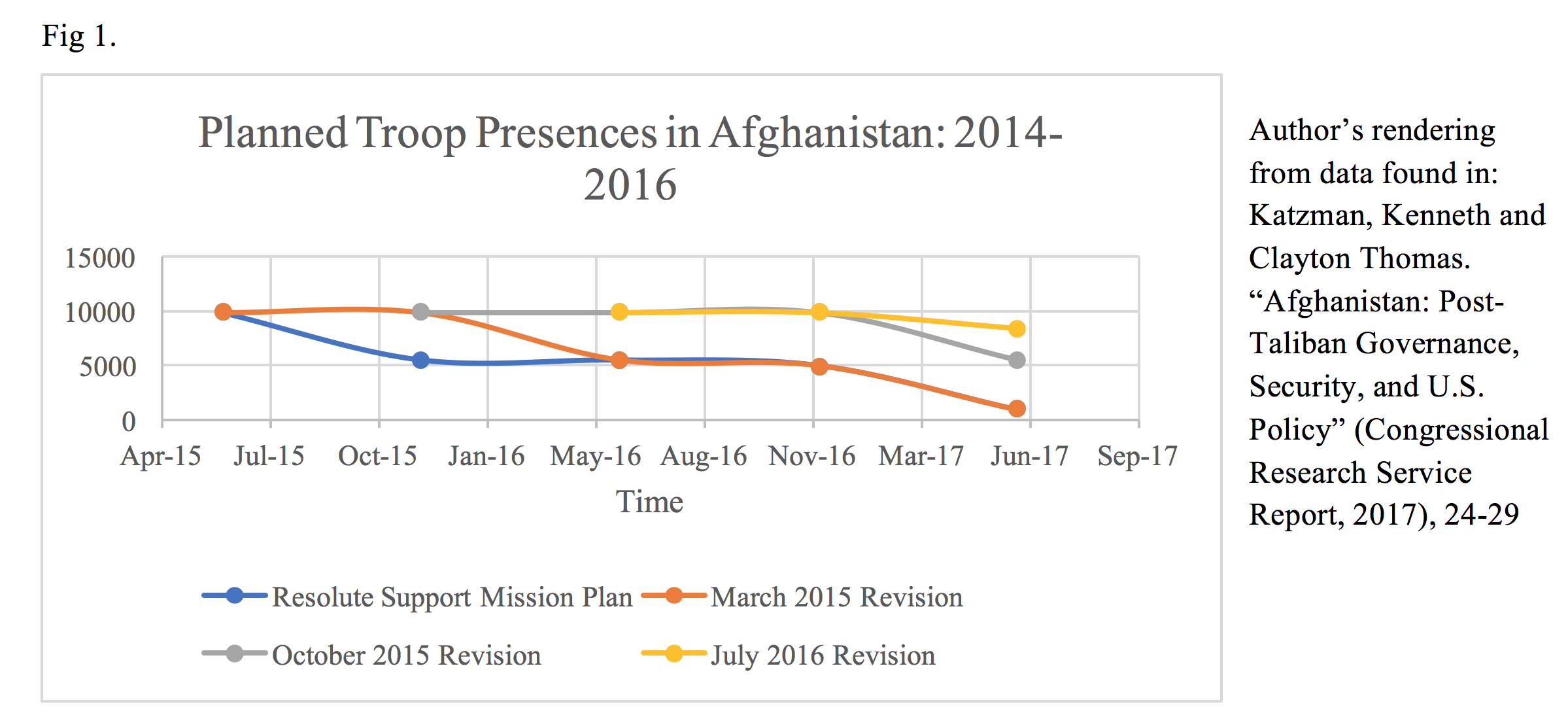

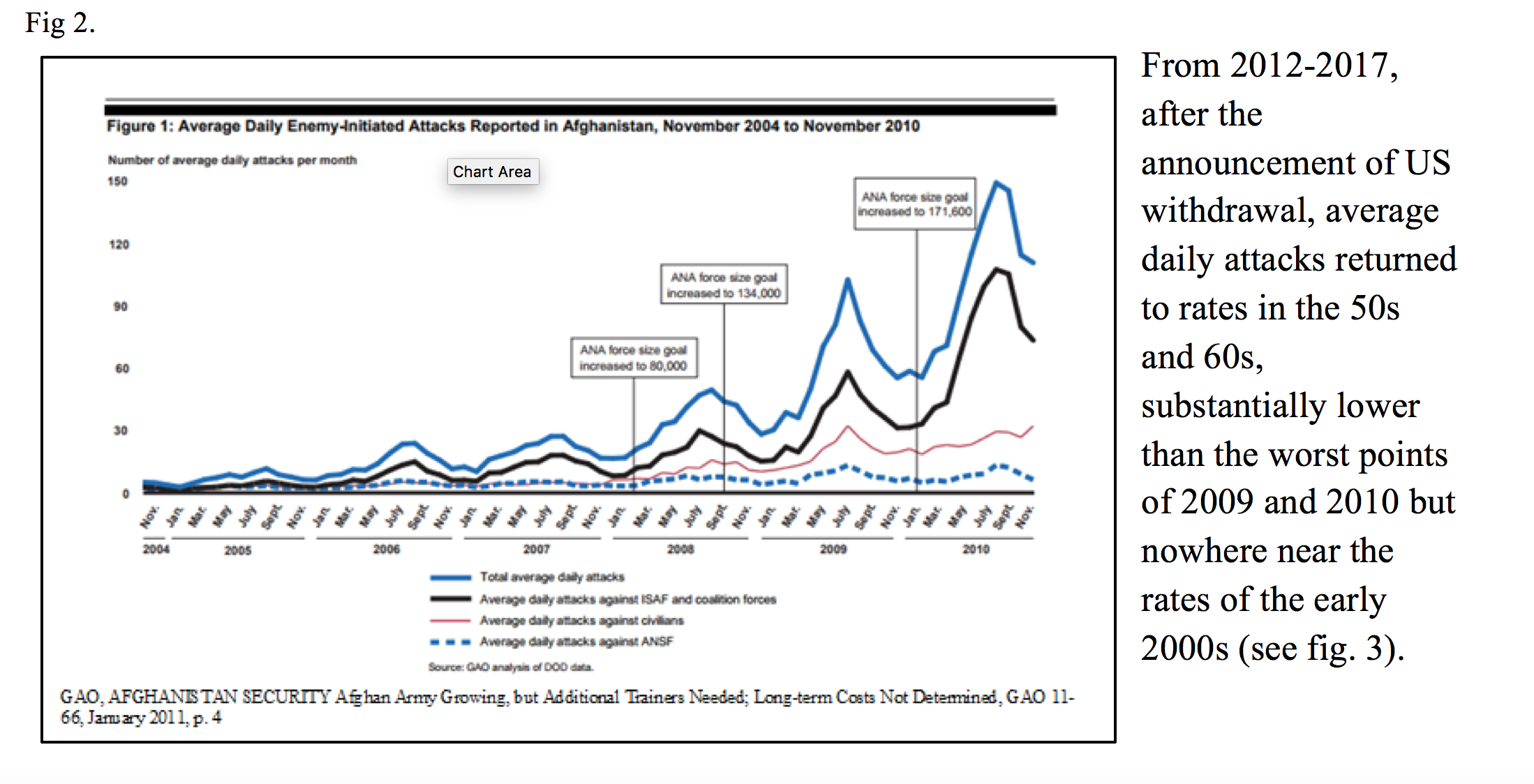

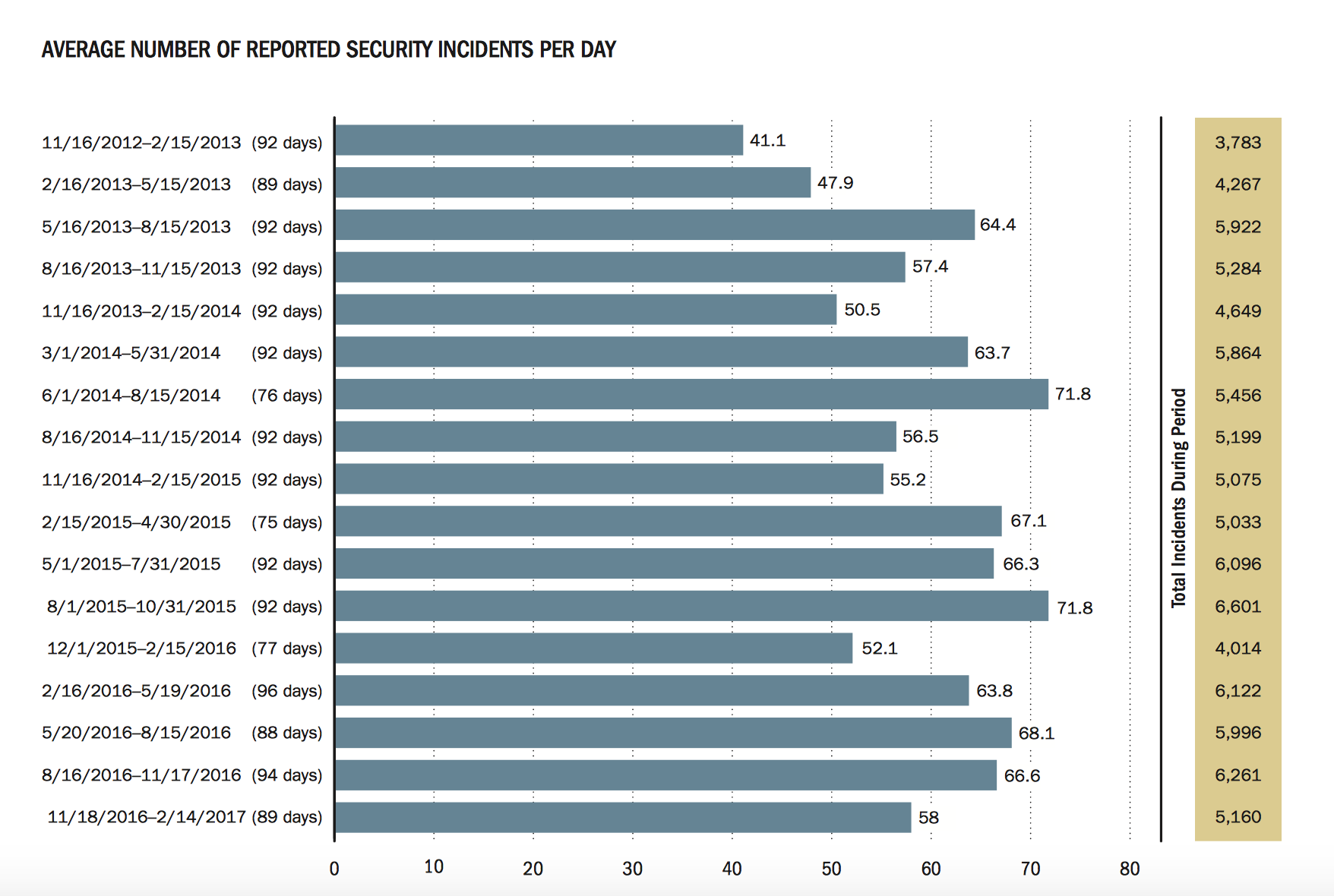

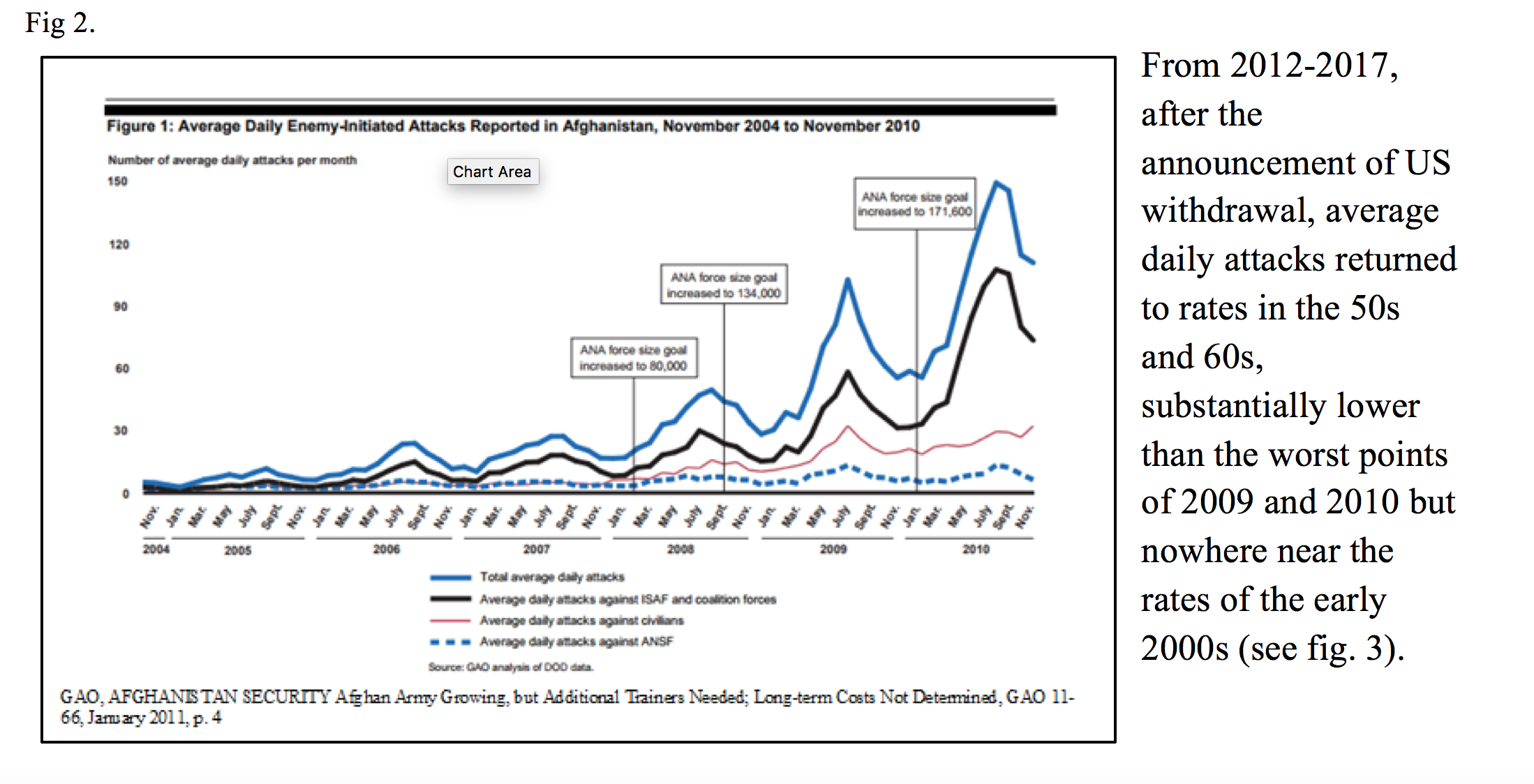

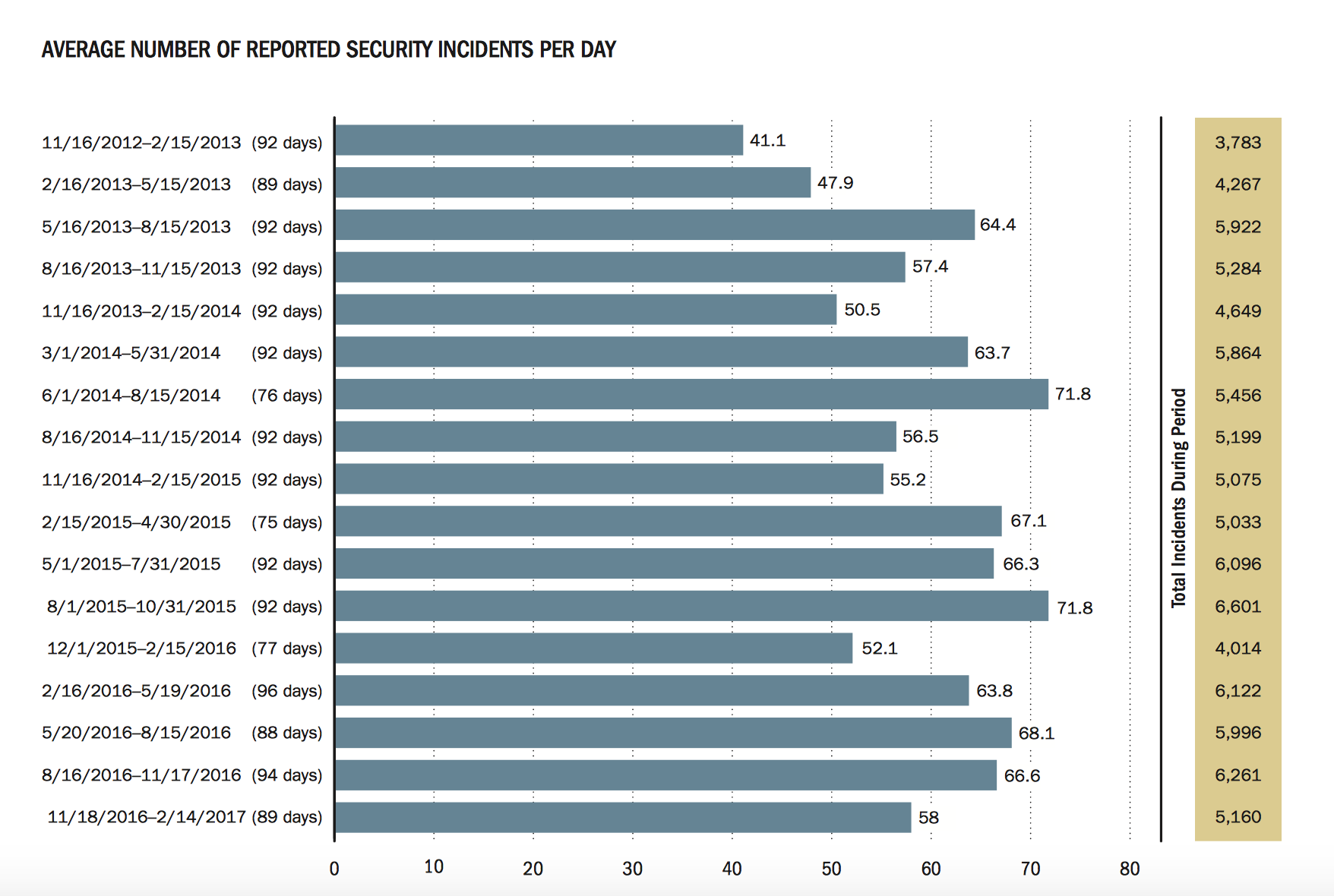

During US operations in Afghanistan from 2003-2009, insurgent attacks were steadily on the rise[1]. In the earlier part of this time period (2004-2007) average daily attacks hovered under 30, but in 2008 they broke that barrier and continued increasingly rapidly, reaching their highest point in 2010 (see fig. 2).

Figure 2

Figure 3

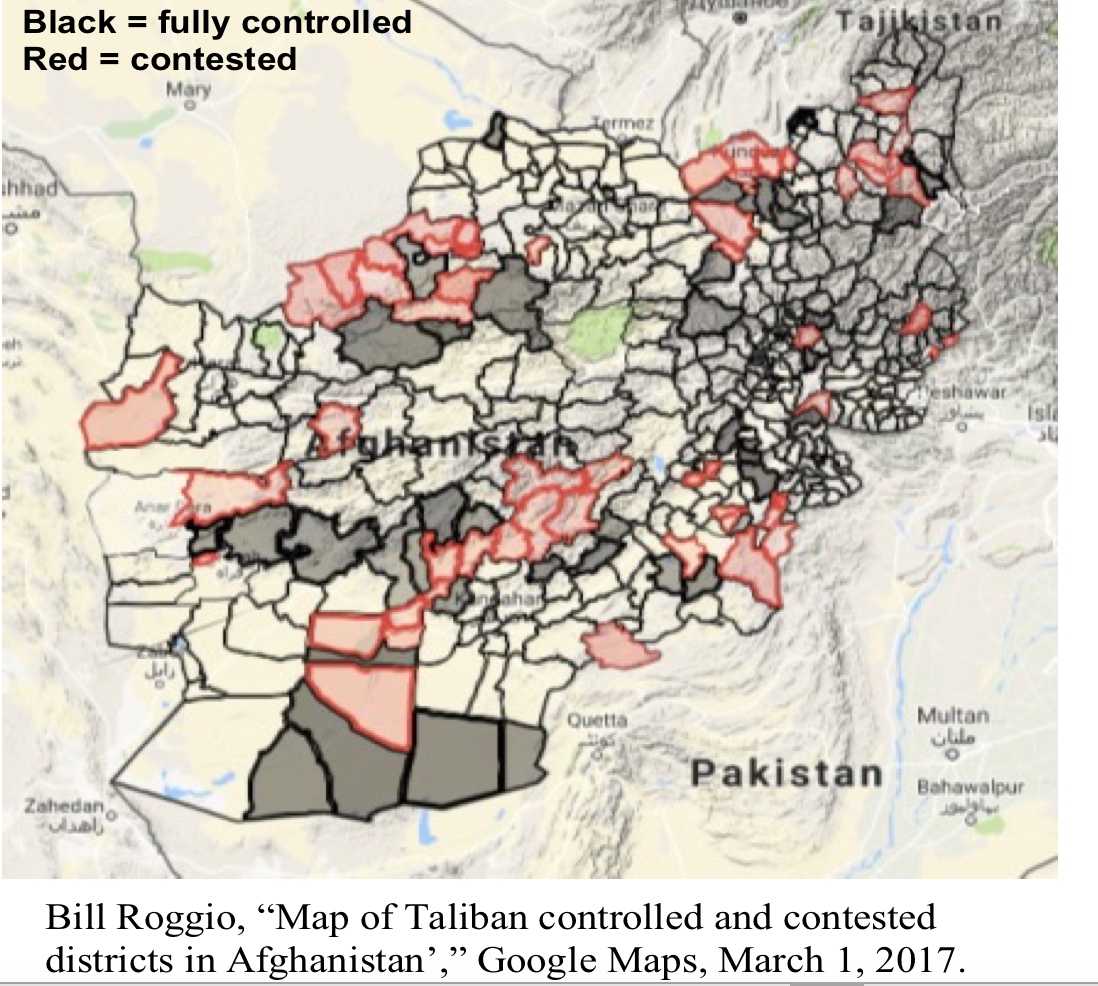

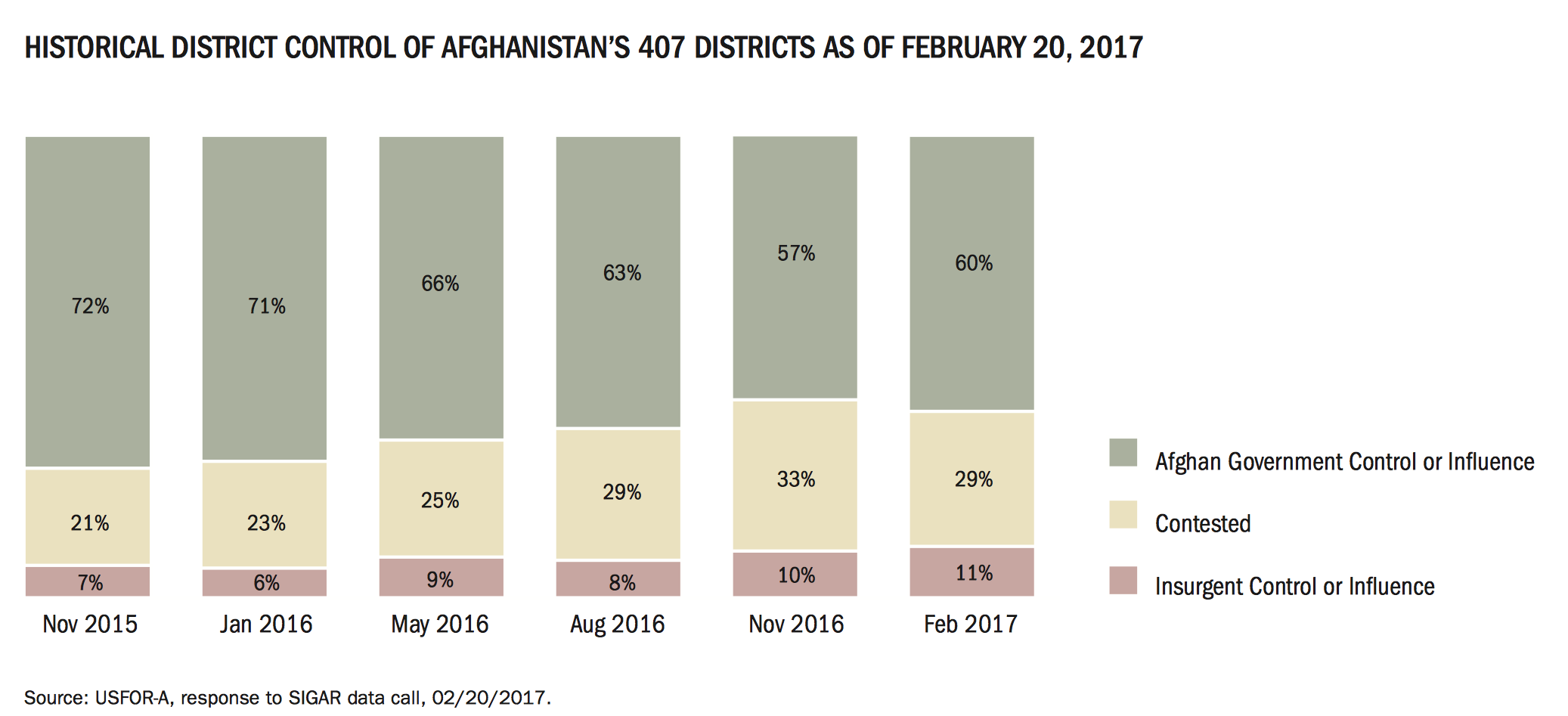

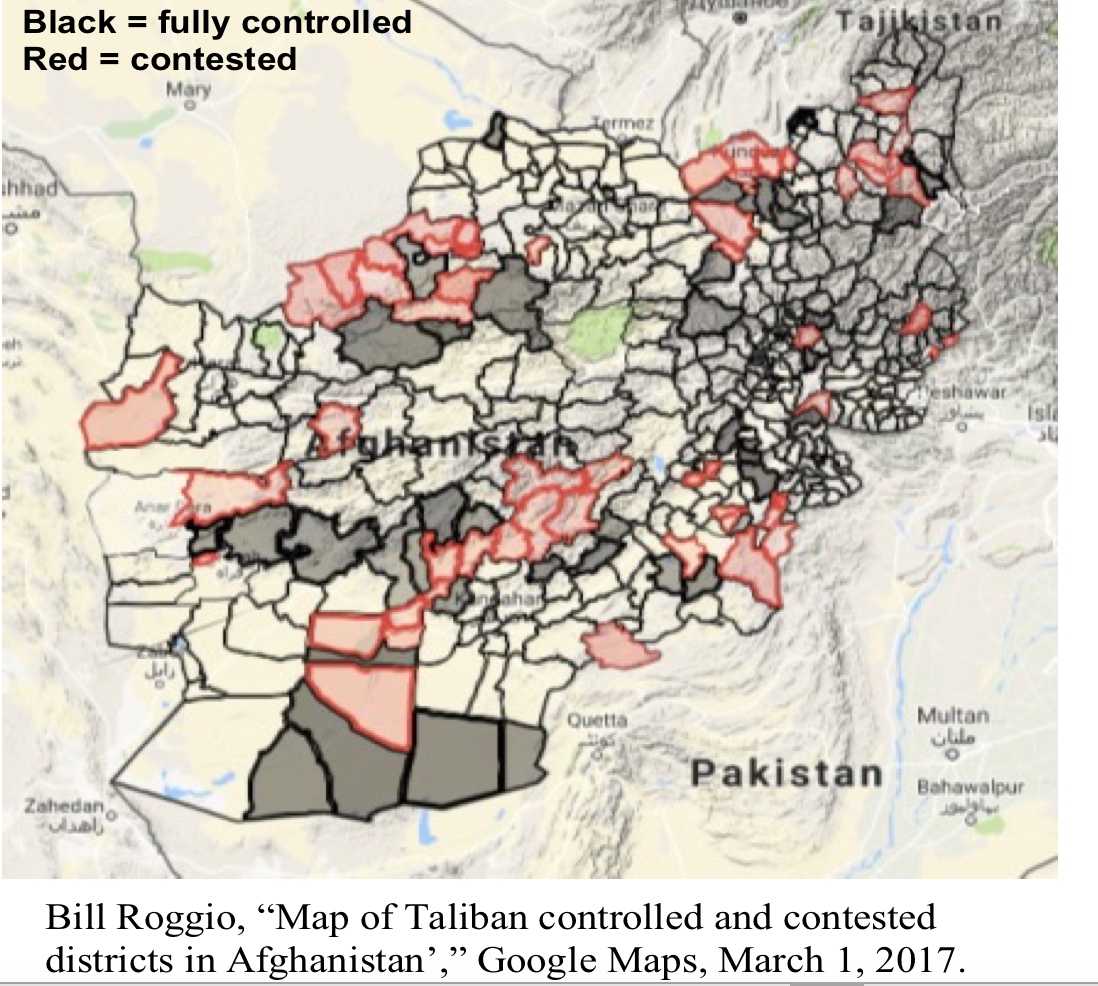

What may be of greater concern, however, is militant control of territory. Since 2015, areas under insurgent control have been incrementally increasing while areas of government control have decreased substantially (see fig 4&5). By September 2016 the Afghan government controlled approximately 68%-70% of the population, the Taliban controlled 10%, and the remainder was contested[1]. Government control is mostly concentrated in urban population centers, while the Taliban is strongest amongst rural populations5.

Additionally, Afghan forces have recently suffered high casualties5. In 2016, the Afghan National Defense and Security Forces (ANDSF) logged 6,700 combat deaths, a 21% increase over the previous year[2]. This, combined with the fact that 35% of the ANDSF does not reenlist after their first tour, leads to concerns about whether the ANDSF has sufficient resources to effectively combat the Taliban without US assistance6.

Figure 4

Figure 5

New Strategy

President Trump’s remarks on the administration’s strategy in Afghanistan and South Asia suggest three major deviations from previous operations. One is a switch from a time-based to a conditions-based approach to withdrawal. Two is an increase in pressure on Pakistan to stop harboring Afghan militants. There is a rejection of nation-building in favor of simply “killing terrorists”[1].

Conditions Approach

The Trump administration’s decision to leave troops in Afghanistan until “conditions on the ground”7 warrant their withdrawal reflects concerns around Iraq’s continuing struggles with ISIS. The US’s decision to leave Iraq completely after 2011 has been blamed by many for creating the power vacuum that allowed ISIS to thrive3. President Trump articulates a related concern about insurgent forces feeling that they can “wait us out”7.

While sound in theory, this approach leaves several areas of concern. First is the ambiguity of what conditions must be met for the US to withdraw. If the ultimate goal of continued US involvement is to ensure that the ANDSF is able to control Afghanistan on their own and to remove the substantial insurgent threat, an objective definition of what that looks like is essential to any strategy. There is widespread agreement that a time-based approach led the US to begin withdrawal prematurely, but a conditions approach is not immune to that problem if the conditions are poorly or inaccurately defined. The necessary elements for a lasting peace in Afghanistan are difficult to pin down, but would likely include factors such as the percent of territory contested versus under government control, the casualty levels among ANDSF forces and the projections of their force strength, and the stability and legitimacy of Afghanistan’s government, especially among rural populations. Without laying out specific goals in these and other areas a conditions approach cannot function as a viable strategic approach.

Pakistan

President Trump’s remarks indicated that Pakistan’s involvement in insurgent activity will be a major factor in US actions in the region, and with good reason. Even if every Taliban and Islamic State fighter was removed from Afghanistan, a lasting peace would be impossible if they remain on the other side of the Durand Line.

Pakistan’s primary goal at all times is relative power over India, and its activities in Afghanistan depend on how it feels that goal is best achieved. Historically, Pakistan has viewed the Afghan government as too sympathetic to India and supported insurgents in order to weaken a potential Indian ally and create a sphere of influence for itself. These concerns are unlikely to be alleviated by President Trump’s declaration that “another critical part of the South Asia strategy for America is to further develop its strategic partnership with India — the world’s largest democracy and a key security and economic partner of the United States“7.

It’s unlikely that Pakistan will ever be fully willing to relinquish ambitions of holding influence over Afghanistan against India. Therefore, the best path to peace is to force them to settle by making supporting insurgents inconvenient and ineffective. The tide may be turning already, as reports indicate that Pakistan is beginning to find Afghan instability taxing due to the refugee situation it has created[1]. US efforts to block any path the insurgent success in Afghanistan will continue to eliminate remaining incentives for Pakistan to harbor violent insurgents. However, it is also worth noting that even if Pakistan enthusiastically cooperated with denying refuge to Afghan insurgent groups, Pakistan has its own militants to combat, and may be stretched too thin to effectively deal with Afghan insurgents as well. Indeed, testimony by US officials indicates that the Pakistani military has issued orders to deny safe haven to Afghan insurgent groups, but is unable to direct resources to actively combat them8. In short, a Pakistan hostile to a stable Afghanistan will be a major hindrance to US interests in the area. Linking a stable Afghanistan to a stronger India is almost certain to create such a condition. At the same time, the US needs assurances that Pakistan will not harbor insurgents while still being aware that, even with full cooperation, that may be an unattainable goal.

Nation Building

President Trump’s remarks on nation-building in Afghanistan are some of the most nuanced and complicated, and yet may be the most important to predicting future stability in the region. His statement that the US will “no longer use American military might to construct democracies in faraway lands, or try to rebuild other countries in our own image”7 speaks to two common concerns about US presence in the Middle East. The first is the issue of cultural sensitivity. President Trump goes on to say that “We are not asking others to change their way of life,”7, in other words, assuming a level of western superiority and trying to rebuild Afghanistan according to a standard of civilization that fails to account for equally valid cultural differences. Such concerns are valid and important to informing an equitable and effective strategy in the area. The US must strike a balance between defending universally recognized rights and values while allowing for differences. The second concern is costly involvement with no benefit to the US. International aid can easily be interpreted as using taxpayer money for charitable hand-outs to other countries. President Trump’s references to “shared interests” and “principled realism” indicate that he is thinking in those terms7. The question then becomes what, if any, aid is essential to securing these “shared interests,” which presumably include a stable and widely legitimate Afghan government and an end to insurgent violence. Evidence indicates that at least some level of practices that would fall under “nation-building” is necessary to those interests. A good example is the ANDSF. Department of Defense reports

The question then becomes what, if any, aid is essential to securing these “shared interests,” which presumably include a stable and widely legitimate Afghan government and an end to insurgent violence. Evidence indicates that at least some level of practices that would fall under “nation-building” is necessary to those interests. A good example is the ANDSF. Department of Defense reports express concern regarding widespread illiteracy among the force and how it might inhibit its combat effectiveness. In this case, security would benefit from measures to improve education systems in Afghanistan. On a larger scale, feelings of abandonment could have very real security implications for the US in the future. In the past, the perception throughout the Middle East has been that international powers, the US included, have fought for their own interests there and then left the countries in tatters when their mission was accomplished. Extremists groups have proven adept at capitalizing on these feelings. Therefore, devoting some resources nation-building is essential to creating a lasting peace.

Conclusion

The Trump administration’s articulation of its Afghanistan strategy is still in its early stages. So far, three key change has emerged: conditions approach in determining the appropriate time to withdraw, a doubling down on Pakistan’s activities, and a cessation of nation-building. Given the deterioration of Afghanistan’s security situation after the US began withdrawing troops in 2014, changes of some kind are clearly needed, but whether the new strategy will be able to implement the right kind of changes and succeed in bringing peace to the region remains to be seen.

——————————————————

Endnotes

- “Timeline: The US War in Afghanistan,” Council on Foreign Relations, 2017 https://www.cfr.org/timeline/us-war-afghanistan

- Katzman, Kenneth and Clayton Thomas. “Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy” (Congressional Research Service Report, 2017), 7

- Katzman, Kenneth and Clayton Thomas. “Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy” (Congressional Research Service Report, 2017), 24-29

- “Afghanistan Security: Afghan Army Growing, but Additional Trainers Needed; Long-term Costs Not Determined” (United States Government Accountability Office Report to Congressional Addressees, 2011), 4

- General John W. Nicholson Jr. (Commander, Resolute Support and U.S. Forces Afghanistan) in a Department of Defense Briefing, September 2016

- Katzman, Kenneth and Clayton Thomas. “Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy” (Congressional Research Service Report, 2017), 32

- Donald Trump “Remarks by President Trump on the Strategy in Afghanistan and South Asia” (Arlington, VA, August 21, 2017)

- Katzman, Kenneth and Clayton Thomas. “Afghanistan: Post-Taliban Governance, Security, and U.S. Policy” (Congressional Research Service Report, 2017), 45

https://fas.org/sgp/crs/row/RL30588.pdf

https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/08/21/remarks-president-trump-strategy-afghanistan-and-south-asia

http://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/afghanistan-partial-threat-assessment-november-22-2016